The history of the founding of the Grammar school is tied up with the early fortunes of the Colony of Sierra Leone and the early history of the other Institution founded by the Church Mission Society around the same time, the Christian Institution that became Fourah Bay College (FBC).

The CMS started in 1799 as the “Society for Missions to Africa and the East”. It was founded by the Abolitionists, people like William Wilberforce and Henry Thornton who was the first treasurer of the new society, and Chairman of the Sierra Leone Company which ruled Sierra Leone at its inception. The name of the society was later changed to the CMS. Soon after it’s founding, the CMS turned its attention to Africa and its first missionaries were sent to Africa in 1804. The attention to Africa was greatly stimulated by the founding of the colony of Sierra Leone and a sense of commitment of its founders and early sponsors to bring their own version of advancement to the new settlement. Thus their first effort was a mission station around that area, in the Rio Pongas where an earlier missionary’s offer to do translations from Soso decided the issue. The Rio Pongas mission failed to make any dent in an area dominated by Islam and the Sierra Leone colony thus quickly became the main focus for Christianity and its attendant educational efforts.

The CMS had started a Christian Institution at Leicester in 1815, intended for “the maintenance and education of African children and for the diffusion of Christianity and useful knowledge among the Natives”. Temporary buildings were erected on Leicester Peak and the school started in 1816 with about 350 children of both sexes. They were being taught basic crafts with a heavy emphasis on Christianity. The Institution literally collapsed in 1820 and its buildings were converted into a hospital for Liberated Africans. The Institution was transferred to Regent but on the death of the Rev W.A. B. Johnson who supervised the school, the Christian Institution was abandoned in 1826. In 1827, the CMS sent Rev. Haensel to revive the Institution to serve as a feeder to a proposed college at Islington, England where they would obtain higher education. The Regent buildings being beyond repair, The CMS bought property of late Governor Turner at what was called Farren Point at Fourah Bay for 330 pounds and thus the Fourah Bay College started as a revival of the Christian Institution. The intention by this time was to provide as high a standard of education as possible, preparing its products to be teachers and missionaries to their own countrymen. Instruction included Reading, writing, music, arithmetic, geography and a healthy dose of Bible history and doctrines. The initial emphasis on crafts in the Christian Institution had thus been abandoned and the first products of Fourah Bay actually found difficulty gaining employment in a fledgling colony, which had very few positions for people with their kind of education.

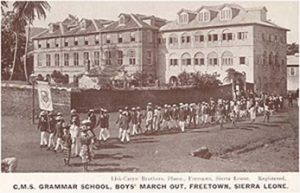

By the 1840s, it had become evident that the academic standard of Fourah Bay College was getting much higher than that which obtained in the regular school system. This meant that it would become difficult to recruit new entrants into FBC from the existing school system. It was therefore necessary to establish a second tier school, the real meaning of secondary school, to bridge the gap between the primary schools and the College. As the CMS began to actively pursue this idea, it received assistance from another organization in London called “The African Native Agency Committee” which provided 150 pounds sterling per annum for a three-year period to train four African youths at FBC or at the proposed grammar school. Thus the CMS pressed on with the plan and procured land at Regent Square in Freetown, the source of the famous term, Regentonian. It should be interesting to note that this building, offered by the colonial government at an annual rent of two shillings and sixpence, a token sum, used to be the residence of the Governor of the Colony until 1841, just four years before the Grammar school started. It used to be called the “house of arches” due to the imposing arches on all sides of the building.

From 1840 -1858, FBC was headed by Rev. Edward Jones, an African American who provided opportunities for the students to train as teachers by apprenticing them to teach in Sunday schools and employing them as district visitors. It was in Rev. Jones’ tenure that the Grammar School was born. Fourteen junior students of FBC were transferred from that college to start the Grammar School. Let us make an analysis of those 14 foundation pupils. Five of them came from the Gallhinas. Two of these five had previously been at FBC two years earlier, the sons of one of the rulers of the Gallhinas and their last name was Gomez. The other three had only recently been secured by the CMS after one of the schooners fighting against the slave trade in the Gallhinas had brought these boys to Freetown with the approval of their father, the Gallhinas king. The CMS hoped that these boys would serve as a beacon for the spread of Christianity to those areas if they were given western education and Christianity. Thus the idea of educating the sons of rulers in the interior as a means of advancing western values and Christianity to those areas, the same idea that later led to the founding of Bo School in 1906, had found a ready pursuit in the Grammar School.

Of the other nine foundation pupils, three of them – Joseph Flyn, Charles Macauley and Charles Nelson – were from Kissy. Daniel Carol came from Freetown and Robert Cross, who was a man of thirty when enrolled, came from Fourah Bay. Two others, James Quaker and Thomas Smith, came from Kent. One student named Frederick Karli came from Port Loko. The Port Loko entrant needs some explanation. Missionary work had started in 1840 at Port Loko by the Rev. Schlenker leading to the establishment of a Church and school there. In all then, six of the foundation pupils or 43% of them came from what became the Provinces of Sierra Leone. The Grammar School could thus be said to have pioneered the way towards a much more forceful movement towards national integration even at its very inception in 1845.

The first principal of the school was Rev. Thomas Peyton and the curriculum represented a high standard of grammar school education with subjects in English grammar and composition, Greek, mathematics, geography, Bible history, astronomy, doctrine, English history, writing and music. Latin was later introduced as a voluntary class subject. Euclid and algebra were added later still. The early pupils distinguished themselves earning favorable comparisons between their performance and those of English students from Principal Peyton, at a time when racist perceptions of African mental inferiority were very high. The establishment of Christianity was a dominant focus of the new dispensation so that the new pupils had to become Christians.

The Grammar School set the tone for secondary education throughout Sierra Leone and West Africa, particularly because for twenty years it was the only secondary school in West Africa. By 1849 its roll included pupils from the entire sub-region of West Africa many of them fee paying students while a few were financially supported by the CMS, the African Native Agency mentioned earlier and some philanthropic bodies. At the end of 1850, the enrolment was fifty-five scholars.

The Sierra Leone Grammar School was also in the forefront in teacher training a few years after its inception. The school was divided in the 1850s into a teacher training section on the one hand, and on the other a general education and FBC entrance preparation section. In the teacher training section students took English, arithmetic, geography, western civilization, scripture, history and school management. To these same subjects were added mathematics, classics and Greek Testament in the general education and FBC entrance preparation section. The Grammar school thus led the way in training teachers for particularly the primary schools in Sierra Leone and this gave a tremendous boost to the quality of primary education in Sierra Leone. The Grammar school also supplied the educated cadres to what became the backbone to the incipient middle class in particularly the British West African colonies in the Gambia, Gold Coast and Nigeria.

One notable deviation occurred with respect to the mainstream education for which the Grammar School had become traditional. Under the principalship of Rev. James Quaker, a printing press was started in the school in 1871. The instructor in charge of the press was named Mr. James Millar and he hailed from Waterloo. The press gave birth two years later to a twice-monthly newspaper titled “The Ethiopia” edited by the Principal. The choice of “Ethiopia” is significant here, for educated Africans in the Diaspora as well as in Africa identified their indigenous advancement with Ethiopia, the oldest surviving independent state in Africa, the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of the world. This was undoubtedly an expression of African aspirations in the new dispensation of colonial rule, which came very early in Sierra Leone. The newspaper brought even greater popularity to the Grammar School. It brought resources too, for the finds that it brought in made it possible for some of the school’s staff to be supported to acquire further training at Institutions in England like the one at Islington. Again, the Grammar school had pioneered in Africa one of the pillars of democracy, a vibrant press.

Similarly so it was the Grammar School, which pioneered the Boys Scout Movement in Sierra Leone, for that movement was initiated by Principal G.G. Garrett in 1908, only one year after the parent movement was started by Lord Baden-Powell in England.

In as far as the academic tradition remained, the Sierra Leone Grammar School excelled and has continued to do so.